I aim to understand why organisms have adapted to their environments in such remarkably diverse ways. Unfortunately, achieving this goal is difficult: most evolution has occurred in the past, and ongoing evolution often takes longer than a human lifetime to observe. Therefore, answers to very basic questions – why do some organisms have sex? why do some outcross and others self-fertilise? why are some haploid and others diploid? does adaptation rely on pre-existing variation or new mutations? – remain elusive. Fortunately, we have tools to overcome this: a century of mathematical models of evolution, allied with new genomic datasets and experimental systems where we can manipulate and observe evolution. I use these tools to investigate principles of evolutionary adaptation.

I have particularly explored the following topics:

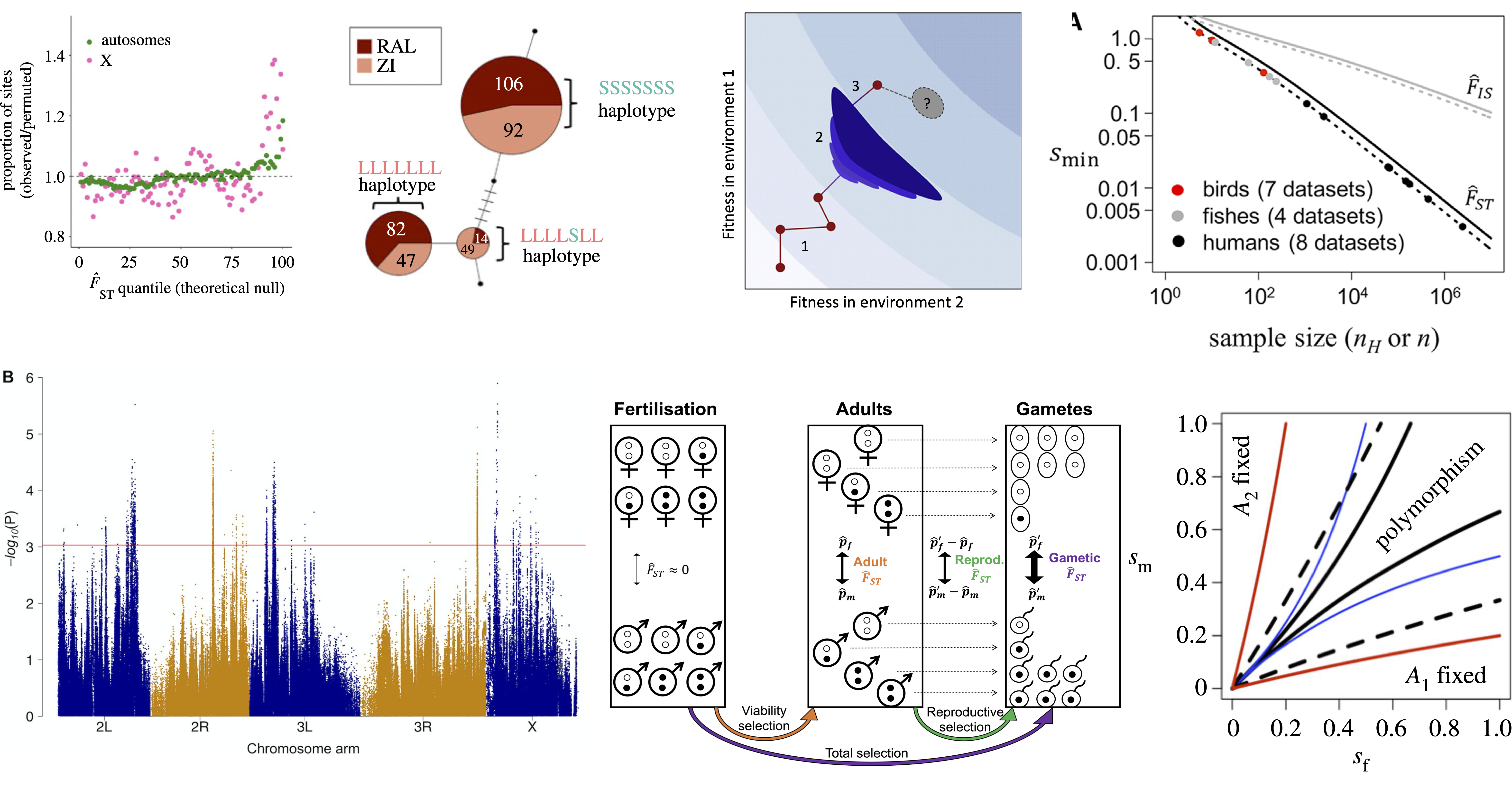

Genetic constraints due to trade-offs between sexes

Sexual dimorphism is a particularly dramatic form of adaptation, yet males and females share mostly the same genome. To better understand the genetic constraints on the evolution of sexual dimorphism, I have extensively studied sexually antagonistic variants (variants that have opposing effects on fitness between the sexes). We identified sexually antagonistic variants in the Drosophila melanogaster genome using a genome-wide association study (Ruzicka et al. 2019). We also went on to develop new methods to detect sexually antagonistic variation across a complete life-cycle, and tested this new theory in humans (Ruzicka et al. 2022) and other species (Ruzicka et al. 2020). And we have considered the extent to which alleles subject to trade-offs contribute to evolutionary divergence (Connallon et al. 2025)

Genetic constraints due to dominance

Dominance occurs when variants are incompletely expressed in heterozygotes, yet we know little about the typical dominance of new adaptive mutations. A basic prediction is that adaptive mutations should be dominant, yet current inferences based on relatively faster rates of X-linked adaptation suggest the opposite. As a first step toward resolving this puzzle, we showed that existing patterns of X/autosome adaptation are potentially compatible with dominant adaptive mutations, provided such mutations have sufficiently large effects (McDonough et al. 2024). My current work uses the ranking of mutations by the magnitudes of their effects on proteins to test the theoretical prediction that faster-X divergence becomes more likely for large-effect mutations.

Sex chromosomes as a lens to study evolution

Sex chromosomes provide a unique opportunity to study evolution because of their asymmetric transmission between the sexes. Using contrasts of X chromosomes and autosomes, we have examined sex differences in the fitness effects of deleterious mutations (Ruzicka et al. 2021), the genomic distribution of sexually antagonistic variation (Ruzicka and Connallon 2020, Ruzicka and Connallon 2022) and the genomic distribution of inversions that capture locally-adaptive alleles (Connallon et al. 2018).

The forces that maintain fitness variation

An unresolved question is the extent to which balancing selection maintains genetic variation for fitness. Our work on sexually antagonistic variation in Drosophila (Ruzicka et al. 2019) and humans (Ruzicka et al. 2022) linked inferences of sexually antagonistic selection to the maintenance of polymorphism. Recently, we have reviewed a century’s worth of theories of balancing selection—due to heterozygote advantage, negative frequency-dependence, and various forms of trade-off between selective contexts (Ruzicka et al. 2025).

Linking mathematical theory with genomic data

In evolutionary biology, the connections between theory and data are often loose (e.g., empiricists often rely on verbal models; theoreticians do not always generate empirically testable models; see Haller et al. 2014 and Fitzpatrick et al. 2018, BioScience). My research continually seeks to bringe mathematical models and genomic data analyses.